The earliest days of West Asheville

Emily Cadmus, MA

Public Historian

The beginning of development in West Asheville is often attributed to the “discovery” of sulphur springs by Robert Henry and a man he enslaved named Sam. Prior to Henry, Indigenous people had been living in the area for thousands of years, making it unlikely that no one had ever happened upon the springs before. According to one history of the area published ca. 1950, there used to be a travel route, established by Indigenous people in pre-colonial times, that traversed what is now known as Hominy Creek. The author, Dr. Gail Tennant, claims that the footpath “crossed from the east into the present Buncombe County at Swannanoa Gap. According to an article by Myer in the 42nd annual Report of the American Bureau of Ethnology, it was the western end of the only ancient route that crossed the state from east to west beginning at the coast.”1 Tennant goes onto describe the landscape of West Asheville and the surrounding area during that time: “The nature of the landscape that met their eyes was not a dense virgin forest…bottomlands were extensive as along the Swannanoa, lower Cane Creek, Mills River and especially along the upper French Broad, there were prairies, large for a mountain country and, wherever the terrain was low, rolling hills, as in West Asheville and most of the Hominy Valley…Chestnuts, black walnuts, and butter nuts formed a substantial part of the Indians’ food and it was only in the openings that these trees bore heavy crops.”2

“Map of Path,” originally published ca. 1950, digitally published by D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.

“Map of Path,” originally published ca. 1950, digitally published by D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.

In 1787, Captain William Moore was granted a title to some land that had been seized from the Cherokee by the state of North Carolina, located near to the Hominy Creek location where he had camped during Rutherford’s campaign. He built a cabin there where he raised twelve children with his wife, Margaret Patton. He enslaved laborers to farm the land, and served in various municipal and civic roles in Buncombe County for the remainder of his life.8 The parcel is located on present day Sand Hill Road, and is designated with a historical marker.9

By 1827, Robert Henry and Sam, a man he enslaved, did happen upon the sulphur springs located in the vicinity of present day Malvern Hills neighborhood.10 Robert Henry was one of the earliest residents of Buncombe County, and like many of the founders of the county, he quickly acquired large amounts of undeveloped land that was made available to citizens of the fledgling United States after it was seized from Cherokee people during and after the Revolutionary War. By the time Robert Henry and Sam stumbled upon the sulphur springs by Hominy Creek, Henry had already amassed over 1,100 acres in Buncombe County, almost half of which was purchased directly from the State of North Carolina.11 He worked as a surveyor, a land speculator, a planter, and a public official.12 A review of a biography of Robert Henry on the Buncombe County Special Collections website describes the Revolutionary War veteran as “difficult,” explaining that “he would appear in court barefoot or without stockings. He smoked. He drank far too much. He could be abusive even when sober. He worked slaves on his plantations, mills, and farms.”13

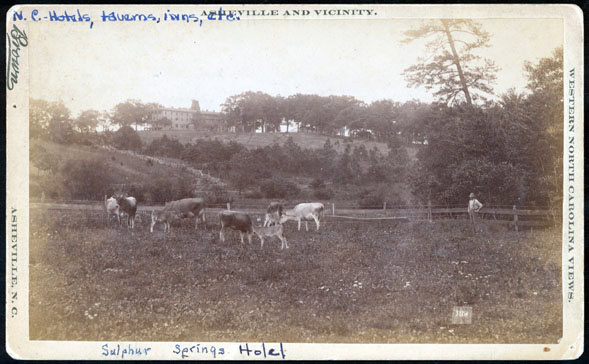

At the time, the area was mostly forests and farmland, but Henry saw economic potential in the development of his land at Hominy Creek. Despite the reputation of his foul temperament, Henry decided to endeavor into the hospitality industry and capitalize on the healing qualities of the sulphuric waters by building a hotel and resort with his son-in-law, Reuben Deaver. They started to slowly develop the land, draining fields, building fences, felling trees, and accepting boarders in their family home. The first guest house was built in 1832, and by 1840, the resort had expanded operations and could accommodate up to 200 guests, solidifying a new influx of health tourism to West Asheville.

Asheville Messenger (Asheville, North Carolina) · Fri, Aug 28, 1840 ·Page 4

Asheville Messenger (Asheville, North Carolina) · Fri, Aug 28, 1840 ·Page 4

According to this advertisement from 1840, Deaver was also subdividing his land holdings in Hominy Valley to vacationers and seasonal residents. By the mid nineteenth century, these visitors would have traveled the Western Turnpike, which went through Asheville, across the French Broad River and going to points further west.14 The route of this turnpike followed present-day Haywood Road, establishing it as a main thoroughfare in West Asheville.15 Deaver was also an enslaver, as were Robert Henry’s son William Henry and his wife Cordelia, who were also involved in the management of the resort. Like many of their contemporaries in the hospitality industry in Asheville and other neighboring places, the Henry’s and the Deavers’ resort was built and run using enslaved labor. This description of the services offered to guests as the Sulphur Springs hotel illuminates some of the types of labor that the people enslaved by the Henry and Deaver family were compelled to perform:

[The resort featured] a barn, cribs for grain storage, house, a machine shop, a well and well house, a smith shop, a poultry house, a smokehouse, and a threshing machine were added. A gristmill was built down at the creek in 1840. Additional outbuildings were built for the comfort and enjoyment of visitors and boarders, including log cabins-the “lower cabins” near the spring, upper cabins and a family cabin with kitchen…[a]horse stable was built , as well as a carriage shelter with an open stable…down the hill from the hotel complex…[was] a bathhouse outfitted with two copper boilers, five partitions with bathing tubs, a water wheel and a reservoir.17

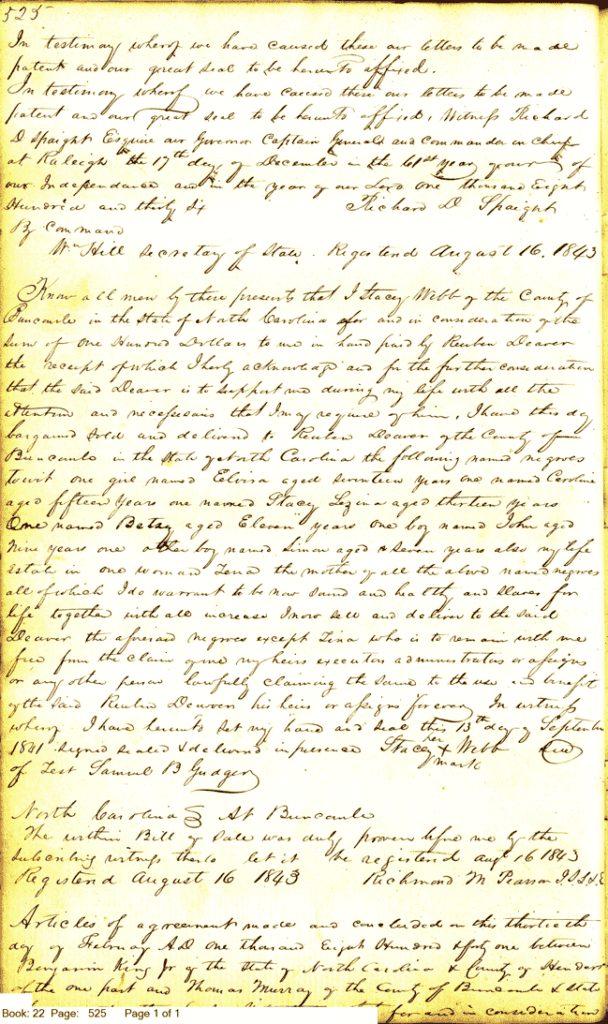

In addition to forced labor, enslaved people’s community network and familial ties were often subject to the whims of their enslavers. This slave deed between Stacy Webb and Reuben Deaver offers a window into this aspect of the experience of being enslaved. The deed describes how Stacy Webb sold six children between the ages of 7-17 to Reuben Deaver in exchange for $100, and the promise that Deaver would provide for Webb in his old age. The children were all siblings. The deed goes on to describe how their mother, Lena, would remain in Webb’s possession as was part of his life estate. In one transaction on the 13th of September 1841, Lena was separated from her six children, without any guarantee that they would one day be reunited.

In the spring of 1861, months before the official start of the Civil War, the Sulphur Springs Hotel burned to the ground, and in 1866, the state of North Carolina repealed its charter for the Western Turnpike.18 These events proved to be a death knell for the Henry and Deaver hospitality enterprise.

In the years after the Civil War Buncombe County, much like the rest of the American south, was in disarray. The economic impact of the Civil War on the south has been well documented, and this time is often reflected upon as a period of stagnation for development. This is true for many city and statewide projects, as well as institutions that had previously relied upon slave labor like the Sulphur Springs Hotel. Alternatively, communities of newly emancipated people initiated a period of rapid development, building churches, schools, new neighborhoods, creating civic organizations, and establishing new systems of economy and mutual aid.

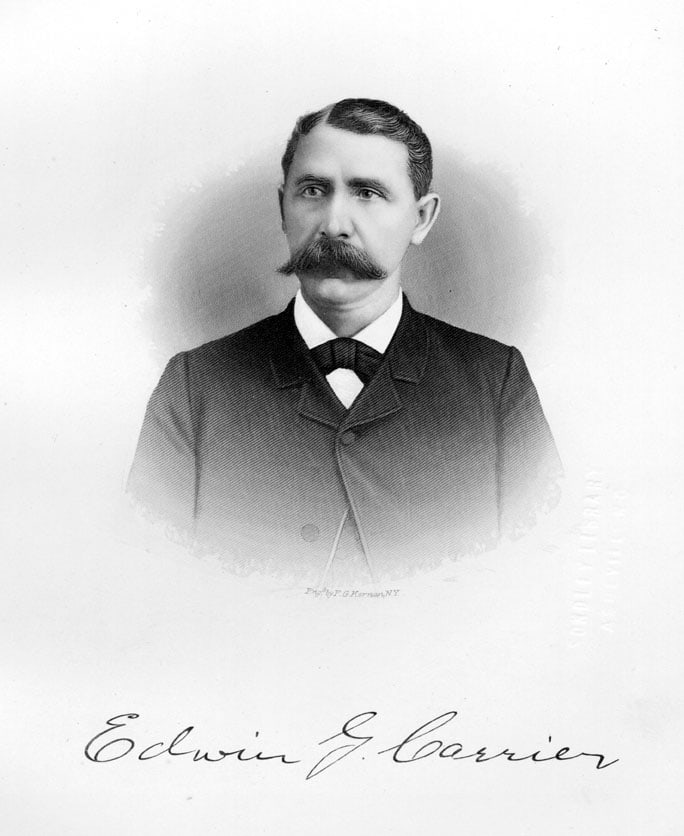

It would be another twenty years, in 1887, before Edwin G. Carrier, a wealthy industrialist and newcomer to Asheville, would reopen the Sulphur Springs Resort. He built a brand new brick facility with the capacity to accommodate up to 300 guests.

Notes.

1. Dr. Gail Tennant, “The Indian Path in Buncombe County,” originally published ca. 1950, digitally published by D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.

2. Tennant.

3. David A. Norris, “Rutherford’s Campaign,” from the Encyclopedia of North Carolina edited by William S. Powell. Copyright © 2006 by the University of North Carolina Press, published on NCPedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/rutherfords-campaign, edited November, 2022.

4. Tennant.

5. Norris.

6. “Letter from Captain William Moore to General Griffith Rutherford, 17 November 1776,” in the Griffith Rutherford Letter #2188-z, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

7. Norris.

8. “William Moore (P-54),” DNCR historical marker database, January 22, 2024, https://www.dncr.nc.gov/blog/2024/01/22/william-moore-p-54, and “Slave Deeds,” William Moore to John Ashworth, sale of Dick, and William Moore to Ann Ashworth, sale of Rachal, July 4, 1817, book H, pages 349 and 350, Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

9. “Captain William Moore,” Commemorative Landscapes, https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/899/.

10. Grady Cooper, “Shifting identity: West Asheville’s storied past,” Mountain Xpress, 2013, https://mountainx.com/news/community-news/040214a-shifting-identity/.

11. Buncombe County Register of Deeds, book 4 page 352, book D page 209, and book H page 225, 1799-1816.

12. David Whisnant, “The Several Lives of West Asheville, Part I: Sulphur Springs as Proto-Land of the Sky, 1827-1861,” Asheville Junction, blog, September 11, 2016, https://ashevillejunction.com/the-several-lives-of-west-asheville-part-i-sulphur-springs-as-proto-land-of-the-sky-1827-1861/.

13. Richard Russell, “Robert Henry: A Western Carolina Patriot,” Buncombe County Special Collections Website, November 8, 2013, https://specialcollections.buncombecounty.org/2013/11/08/robert-henry-a-western-carolina-patriot-by-richard-russell/.

14. Charles H. McArver, “Turnpikes,” originally published in the Encyclopedia of North Carolina edited by William S. Powell. Copyright © 2006 by the University of North Carolina Press, digitally published on NCPedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/turnpikes#:~:text=Finally%2C%20in%201854%20the%20General,across%20the%20Stansbury%20Mountain%20chain.

15. Cooper.

16. Archival Description, “Henry Family Papers, 1837-1911,” MS020, BCSC Pack Library, 28801.

17. Richard Russel, Robert Henry: A Western North Carolina Patriot, (Charleston: The History Press, 2013) as quoted by Whisnant, Part I.

18. Whisnant, part I.

19. David Whisnant, “The Several Lives of West Asheville Part II: Edwin G. Carrier before West Asheville,” Asheville Junction, blog, November 15, 2016.

20. Buncombe County Register of Deeds book 47 page 459, and Whisnant, part II.

21. Whisnant, part II.